Mayn bubbe's tam

Mayn bubbe's tam

I'm not sure that being mortified by previous generation's tastes is a specifically American Jewish phenomenon. There is, after all, a Yiddish phrase for the phenomenon, mayn bubbe's tam, meaning "my grandmother's taste," which hints that in the old world people were similarly aghast at the tackiness of their ancestors.

In fact, it is possible to argue that the Reform movement was, in part, rooted in aesthetic repulsion at a previous generation's taste -- the early movement sought to remove elements they viewed as "Oriental," included modes of dress, religious melody, synagogue design, and even the form of the service. Tangentially, this is almost a perfect mirror image to the Hasidic movement, whose traditional dress of bekishe coat, halbe-hoyzn knee-breeches, and shtibblat slippers looks deliberately to the East, to Babylon, by way of Turkey.

Come to think of it, the discussion of Hasidic dress is not so tangential, because it demonstrates that Judaism has a long history of both rejecting the past and borrowing from it, and these two histories seem closely bound up with a desire for assimilation and a rejection of it.

I was raised Reform, and am now happily secular, but there is something about assimilation that I find nettlesome. I suppose it is the fact that it always insists on masking or eliminating those things that make someone visibly Jewish -- that we cannot be accepted into mainstream society unless we make Judaism invisible. I also think that this is a strange bargain. We're supposed to get something specific from it -- access to privilege -- and yet Jewish access to privilege is fraught and frequently short-lived, and antisemitism has a long history of punishing Jews for their privilege.

I did an interview on a podcast a few weeks ago. The podcast is called Race Invaders, and I like it very much. The two hosts are Asian American, and struggle with a lot of the same sort of questions I struggle with; there are some surprising parallels between the Jewish and the Asian American experience.

Among them is the risk of buying into whiteness, of becoming a model minority, a phrase originally invented to describe Japanese Americans and later expanded to include Jews, as well as other Asian groups. On a recent episode, the hosts discussed the fact that there are Asian American who resist this model minority status, resist buying into the privilege (and problems) that comes with honorary whiteness.

According to the podcast hosts, as they reject this sort of assimilation, these Asian Americans find themselves looking for an alternative model. And since race in America is so often defined by whiteness and blackness, they end up adopting a lot of black culture. One of the hosts, Alok Desai, pointed out that this raises issues of cultural appropriation, but many Asian Americans are disconnected enough from their own cultural heritage not to be able to use it as a model.

I think American Jews often likewise don't have a model. They especially don't have a secular model. Or they do, but they are embarrassed by it.

There was a recent article in Forward that collected what the author considered to be the worst Jewish album covers of all time. I am not sure what the criteria was in picking these, except that the author found them funny. Some of them are harmless (such as The Jewish Cowboy, an actual and fascinating interview with Harold Stern who ran a Texas ranch, and is only funny if you don't know how common Jews were in the west).

Many are deliberately funny, including Mrs. Portnoy's Retort by the great Mae Questel, a comic answer album to Philip Roth, and several albums featuring the superb comic actor Lou Jacobi. The fact that we still find these album covers funny is a testament to good design, not to terribleness.

The author also seemed to especially have it in for jazz flutist Herbie Mann, whose album design was admittedly a little outre (particular his unclothed and sweaty torso on "Push Push.") But Mann created deeply funky tracks (such as his chart-topping "Hijack"), so not only are his album covers entirely consistent with his style of music, but, honestly, anyone who created a soft jazz version of "Hatikva" (called ""Man's Hope") gets a pass from me for almost anything.

Honestly, I think the sense that these albums are hilarious comes from a combination unfamiliarity and embarrassment over a previous generation's tastes. But when we abandon the previous generation, we assimilate into one of two worlds: An ahistoric one, where there are only contemporary tastes and the past is only worthwhile when it dovetails with modern tastes; or a world of hidden privilege, where the dominant taste is allowed to remain contemporary while minority tastes are left behind.

I think the embarrassment of a lot of the albums listed is the latter: It's not simply that the albums seem out of date, it's that they are so Jewish. The Mae Questel one literally has her surrounded by Jewish food, and there is an album by Theodore Bikel that is entirely unremarkable, except that he is playing Jewish music and his face is lit with red lights.

I suppose I'm a little surprised that these albums provide an aesthetic shock, as they are not mayn bubbe's tam, but my parent's tam -- the albums are mostly from the 50s - 70s, and were in the record collections of many of my friends' parents. More than that, many the comedy albums existed as a sort of monetizing of Jewish embarrassment about the previous generation -- Mae Questel enjoyed a late career revival playing overbearing Jewish mothers, while Lou Jacobi specialized in playing irritable, avuncular older Jewish men.

I'd like to argue against this sort of knee-jerk mortification at a previous generations tastes, especially when those tastes were explicitly Jewish. Now, I'm not arguing for an equally knee-jerk acceptance of it, as I think a sort of uncritical nostalgia can actually be harmful.

I am saying that somewhere in there we can find tools for self-identification that assimilation has buffed away, and shouldn't have.

I'd like to suggest that when we respond to the past with embarrassment, it is sometimes not that the past is embarrassing, but because it represents something that the dominant culture would like us to think is embarrassing. It is embarrassing because it represents nonmainstream tastes or experiences, and one of the ways that privilege protects itself is by declaring challenges to be tacky.

I'd like to dare us to be tacky. I'd like it if we revisited mayn bubbe's tam for the things we thoughtlessly abandoned, and try celebrating them rather than dismissing them.

Because how many photos were taken in the 1970s of shirtless, sweaty musicians? I'm going to go ahead and just guess at a number, and that number is 100 percent. Every single musician on every single album cover in the 1970s was shirtless and sweaty.

So why is Herbie Mann's sweaty shirtlessness especially notable? He's not unhandsome, at least not mores o than everybody in the band SOS, and they are all shirtless on their album cover. The band Orleans basically looks like a group of cavemen, and here they all are, shirtless. Iggy Pop always looked like someone put makeup on a cadaver, and here he is, shirtless. David Bowie isn't just shirtless on the cover of Diamond Dogs, he's half dog.

I suspect the issue is that Herbie Mann is so obviously Jewish, and has a body we associate more with middle-aged Jewish men taking a shvitz than sex symbols, despite the fact that Mann made music that made people make love. But who says middle-aged balding Jewish men are embarrassing, rather than sexy? I ask this as a middle-aged, balding Jewish man.

If grandma found Herbie Mann sexy, maybe grandma was on to something.

Year 2, Week 13: Kishka and tongue sandwiches

Year 2, Week 13: Kishka and tongue sandwiches

The stats:

I have studied Yiddish for 425 days

I have studied Yiddish flashcards for a total of 269 hours

I have reviewed 4,853 individual flashcards

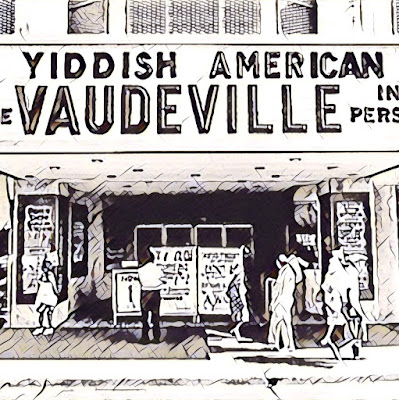

I was in New York for four days, and managed to study Yiddish on three of them, so I'm fairly pleased with myself. The image above is me on Hester Street, which was sort of a metaphor for me when I started this project: Because I was in Omaha, and there was no real Yiddish community around me, I would create a virtual Yiddish community, which I thought of as my own personal Hester Street.

"Hester Street" is, of course, a 1975 film, largely in Yiddish, written and directed by former Omahan Joan Micklin Silver and based on a novella by Yiddish author Abraham Cahan. It's also a street on Manhattan's Lower East Side, and was a center for Ashkenazi Jewish immigrants.

I will be writing about a lot of my New York stuff as separate posts, but I want to just make a note here: There is a great risk in this sort of project of simply giving in to nostalgia, of fantasizing about a past experience of Judaism that somehow seems more authentic than the current version.

I do not wish to do this, and neither do I wish to present New York as somehow being a locus of an older, more authentic Judaism. New York Judaism is one sort of American Jewish experience, and has maintained some elements that are hard to find elsewhere, in part because its Jewish community is comparatively massive.

I am a product of the New York Jewish experience, as both my parents are native New Yorkers and I was a frequent visitor in my youth. But I am also a product of the Midwestern Jewish experience, where we sometimes called delis "dells," and I won't brook having that experience treated as being somehow less authentic.

That being said, there are some vintage Jewish experiences that are just not available to Minnesota Jews. It is not possible to have an Eastern European schvitz -- there are plenty of saunas in the Twin Cities, but they are not that volcanically hot and wet style favored by my ancestors. Local delis do not offer kishka or tongue sandwiches. There is no Yiddish theater.

I hope to be able to recreate some of this here in Minneapolis, and to tell people how they too can recreate it. You may not be able to hire Russian men to beat you with branches where you live, but that doesn't mean you should be denied the pleasures of platza.

I will detail this more in a fuller essay about something called mayn bubbe's tam, or my grandmother's tastes, but for now I will say that as someone who has studied Yiddish in isolation for almost 15 months, it was nice to see a play in Yiddish, and to meet with Yiddishists, and to hear Yiddish in the wild, on the streets.

Judaism is not really something you do in isolation, but instead as part of a community. Language is the same thing. And so it is worthwhile once in a while to go someplace where a community exists that is doing the sort of things that I do in isolation, to see what it looks like, to experience what it feels like, and, perhaps most meaningfully in Judaism, to taste what it tastes like.

Jewish Genealogy: The Genographic Project

Jewish Genealogy: The Genographic Project

I used to teach a class on DNA and genealogy, and maybe I will again at some point. It came from my own interest in the subject. I first had my own DNA tested four years ago, which wound up connecting me with my biological family.

I initially tested myself through a company called 23andme because they also offered testing for genetic illnesses. As an adopted child, I did not know if I had increased likelihood for heart disease, or stroke, or Alzheimer's, or the like. It was rather terrifying to request the results, but I was then in my 40s and figured if long-term planning would be needed, it would be better to know sooner than later.

The test also offered an ethnicity estimate, which I have reproduced below:

As you can see, 23andme has me as almost exclusively European, and largely English and Irish (they do not distinguish). All this was consistent with what I knew from my biological family, which is Irish-American. There are a few surprises in there: Some French and German, some West African, and even a hint of Native American.

23andme is good about letting you know that these results are highly speculative. In fact, you can change the confidence level of the results, and when I switch it from speculative to conservative, all the surprises go away, and I am left with British and Irish and a collecting of generalized European DNA.

I went on to take a few more tests. The next, from Ancestry.com, gave me the following result:

Again with great confidence in my Irish heritage, which is distinguished from the remainder of Great Britain and comes in at 66 percent, and then, with much less confidence, some Scandinavian, Iberian, and even Jewish ethnicity. In another section, they even guess as to the area in Ireland my people come from: Northern Connacht. My people mostly come from County Clare, which is in Northern Connacht, so well done, Ancestry.com.

Of course, they also had access to my family tree, which I created on their site, which explicitly lists my ancestors as coming from Clare, so maybe this isn't that surprising an analysis.

If you have done a previous DNA tests, you can upload your results to Family Tree DNA, so I did that, and they produced their own ethnicity results, which I will not comment on, as they look like this:

I am something of a completist, so recently I submitted a DNA sample (spit; it's always spit) to the Geneographic Project. This is through National Geographic, and I was interested in seeing their ethnicity estimate.

They do it a little differently; the others rely largely on self-reported ethnicity, and so their results are not quite junk science, but, let's say, still in their infancy. People often don't really know their own ethnicity, or only know a part of it, or have been lied to about it. Americans by and large all seem to think there is a Cherokee princess in their background, as though the Cherokee tribe did nothing but produce princesses who all then married white men. So where these ethnicity estimates say "low confident," I am going to say "probably wrong."

But the Genographic Project bases its results on relatively stable populations, and compares your results against the typical results from that region. They don't offer any low-confidence answers. Instead, my results looked like this:

They then compare this against reference populations, to see what countries tend to have a similar result. Mine was most like the results found on the British Islands, although I lack Southwestern European, Northeastern European, and the small amount of Jewish Diaspora DNA found in your typical British person.

My Asia Minor and West Mediterranean DNA is atypical for the British. And I have twice as much Eastern European DNA as your average resident of the British Isles and Ireland.

The Eastern European influence is new -- none of the other tests produced it. And, as someone who spends so much time working on a project based in my adoptive Eastern European heritage, I am delighted that National Geographic has decided I have actual Eastern European DNA. Sixteen percent may not seem like that much, but its a larger amount that a previous test gave me for English DNA (5 percent), and I am not going to stop drinking Old Speckled Hen anytime soon.

There more, too. The Genographic Project, in particular, was created to look into the distant past of genetics, as far back as 100,000 years, through something called Haplogroups, which look back to a single shared ancestors in the distant recesses of the past.

On my biological father's side, I belong to a haplogroup called P305, which belonged to Y-chromosome Adam, an African and very ancient human male. Much later there is U106, which moved into Europe somewhere between 4,250-14,000 years ago, and then finally there is L48, my most recent haplogroup, and a mysterious one, whose age is unknown and is mostly found in Belgium, the Netherlands, and England, among a few other places.

I can follow the evolution of my maternal DNA like this, starting with a haplogroup called L3, which originated in East Africa 67,000 years ago, and then split off into R about 55,000 years ago, which moved into East Asia, and finally turned into K1a sometimes in the last 18,000 years, approximately. It represents only 2 percent of the population of Northern Ireland, but that's my population, right there.

But there is something else there. I am not genetically Jewish. There is not a hint of Ashkenazi Judaism in any of my tests. But I share a common ancestor with Ashkenazi Jews.

You see, before K1a, there is the K haplogroup, which developed in West Asia around 27,000 years ago, and K is the maternal haplogroup most frequently claimed by Ashkenazi Jews.

Let's stop here for a moment.

Let's stop, because ethnicity is not determined by genetics, and neither is religion. There is a real problem, in fact, with people claiming genetic identities with which they have no other connection. I have especially heard complaints about this from Native American and Rom Gypsy authors, who write about ostensibly white people who suddenly discover some distant ancestry and begin to show up at Indian or Gypsy events, claiming membership and even leadership.

Instead, I'd like to suggest that this demonstrates how awesomely complicated our genetic heritages are, and how they can dovetail with ethnicity in interesting, if not definitive, ways.

I am already a Jew, regardless of my haplotype. I am because I was adopted by a Jewish family and raised within a Jewish tradition. I am culturally Ashkenazi, because that is the tradition I was raised in, and pursue an interest in the experience of Eastern European Jews because that is where my grandparents came from, regardless of whether I have a genetic connection with the region or not.

I am also an Irish-American, and am so because I have direct Irish ancestors, and I have spent my life exploring and participating in the Irish-American experience.

I would offer this suggestion to anyone who gets these sorts of tests: Each ethnic group determines its own membership, but it is generally accessed through some combination of familial relationship and participation. If you discover you have a distant genetic relationship with a group that otherwise you have had no experience with, find out what membership means for them before you claim it for yourself.

And realize that these DNA tests are a relatively new science. They are pretty good at communicating the fact that there is tremendous uncertainty in their results -- try to respect that. Because you don't want to run out and learn Lithuanian and buy a Lithuanian folk costume and start showing up at Lithuanian-American events, if they'll have you, only to have an algorithm update and suddenly declare you Polish.

Identity politics is hard enough without throwing in mistaken identity politics.

Play production journal: The Balalaika

Play production journal: The Balalaika

There are quite a few months before the Fringe Festival in Minneapolis -- the event takes place August 3-13. So you would think there is no hurry to get anything done, and maybe there isn't. The festival can be pretty loosey goosey, with shows slapped together shortly before being mounted, and they end up being a lot of fun anyway, their messiness a large part of their charm.

"Shaina" can't be that. There is too much work to do for it. Last week I wrote a grant to help underwrite its production cost, which I currently have figured at $2,000, although things are always more expensive than you expect.

A chunk of that cost is the balalaika, pictured above and already purchased.

The balalaika is not in the script right now. Also, it's not actually a balalaika.

Let me explain:

In the original conception of the play, the title character performs Yiddish theater songs, and so, when she does so, she is joined onstage by a very nervous Hasidic accompanist on piano. The Hasid drags the piano onstage and off with him, and, well, frankly, this is impossible.

Firstly, Fringe venues are small and temporary, so there will be no pianos. Secondly, musicians are expensive, and my budget is small. So I will be the Hasid, and I do not play piano.

I do, however, play another instrument. I am a relatively skilled ukulele player, and, in fact, used to perform around Minneapolis as the Ukulele King, which then somehow morphed into a cowboy show in Omaha in which I was the Ukulele King of the Great Northwest.

Sometimes even I know how preposterous my stories of my life are, by the way.

So the piano has become a balalaika in the script, because that's a lovely old world instrument. I have another balalaika, and it's a fun thing, but they are odd instruments. There are three strings, and two are tuned to exactly the same note. They're quite good as part of a balalaika orchestra, or to play melodies along with a larger band, but it takes an extraordinary degree of sophistication to use it as a solo instrument.

I don't have that sophistication. Not on balalaika. On ukulele, however ...

So the instrument above is actually a ukulele built into the body of a balalaika.

I wrote a bunch of songs for the play, but never wrote any melodies for them, so I will be doing so with the balalaika/ukulele shortly.

Next on my list, though, is revising the script. Fringe shows are best when they are only about an hour and extremely minimal, and so I need to take my already stripped-down script and carve it down to its barest bones.

I don't mind this. I think plays work quite well when pared down. I'm ready to go at it with a chainsaw and a blowtorch. That's the task for this week. Next week, I write the songs.

Year 2, Week 12: It's up to you New York

Year 2, Week 12: It's up to you New York

The stats:

I have studied Yiddish for 430 days

I have studied Yiddish flashcards for a total of 266 hours

I have reviewed 4,821 individual flashcards

I'm going to New York this weekend and won't be lugging my massive Schaechter dictionary with me, but I don't want to have four days in which I add no new words to my collection of flashcards, so I have been working ahead, plugging in as many words as possible.

I think I have added enough to cover me during my trip. Now the challenge will be to see if I can actually peel away the time to study. Although there have been few days in the past 15 months I have failed to study, I have not been faced with the challenge of being in a city as distracting as New York. If I can manage to study there, I suppose I can manage to study anywhere.

I'm going out to New York for a few reasons. The first is that I haven't had a proper vacation in quite a long time and I am overdue. I've been back in the Twin Cities for five months, amazingly, and the move was stressful, as moves always are. I have been settling in at my new job, which has involved a steep learning curve, as happens with a new job.

We have mostly been homebodies since we moved back, largely because it is very cold in the winter and its wise just to curl up someplace warm. But it is starting to warm up, and I am starting to settle in at my job, and it is time to relax a little.

"Relax" may be the wrong word. I will be running around Manhattan a lot. I decided to take this trip, in part, because there is a Yiddish production of "God of Vengeance" and how can I do this project, be a playwright, be producing a Yiddish-themed play, and not take in some Yiddish theater?

There is also a lot of old-school Jewish stuff in New York that I cannot do in Minneapolis -- no tongue sandwiches, no Russian baths, no Yiddish newspapers. So I'll be peeking in on a lot of that stuff, as well as the sorts of things I have grouped in as part of my Jewish identity but are more peripheral. I will be going to a Ukrainian museum, as an example.

I will also likely hit a few Irish bars, although I have done a lot of tours of Irish New York.

I'm not sure why I haven't done this sort of deep dive into Jewish New York before. I suspect it is because it is already so much of who I am: My parents are native New Yorkers, and so I took frequent trips there when I was a boy. I spent a lot of time in New York delis and the like. But the truth is that as an adult I have spent a lot more time exploring the Jewish culture of Los Angeles, where I lived for six years, than that of New York.

I will probably do more of that on my next vacation, which will probably be to Los Angeles.

Having this blog incentives doing a lot more of this as well, as it gives me something to write about and I enjoy writing about it.

And there's something else. I will probably work it up into a more formal essay at some point, as it's still bouncing around in my bean. But I was reading about the Jewish Autonomous Oblast, which was an area in the far east of Russian set aside to be a Jewish region, with Yiddish as the official language (along with Russian). It was a disastrous experiment in a lot of ways, and one of the biggest disasters was that participants realized that Yiddish had been separated from Jewish cultural practices, and, as a result was used to propagandize Soviet ideas to young Jews, encouraging their assimilation.

So Yiddish isn't, in and of itself, enough to support a Jewish identity. Without being wedding to other Jewish practices, it can even serve the opposite purpose and help wean Jews away from the Jewish identity.

And what is identity? I guess I have been coming around to the idea that if your identity is internal, it is just a piece of self-identification that exists inside yourself, that you're Jewish because you know you're Jewish and because you feel somehow Jewish -- well, this strikes me as a weak identity, one that can be hard to maintain and is even hard to pass down to the next generation.

It is a stronger identity if you couple that feeling of being Jewish with actually doing things that are Jewish. I suppose I feel this way in part because my father was a research professor, and so I grew up with Behaviorism, which suggests that our internal world is, in large part, created by our external actions, and not the other way around. That we are what we do.

As regular readers of this site know, my Jewish identity is secular and my religious identity is atheist. So I am always looking for Jewish things to do, or to do things Jewishly, that are not explicitly religious. For the past 15 months, this has largely involved learning Yiddish. But language is just one thing, and, on its own, it is not enough, as the Jewish Autonomous Oblast taught us.

So I am going to New York to find Jewish things to do, or to do things Jewishly. I will report back.

Play production journal: Shaina

Play production journal: Shaina

The first two plays I ever wrote were Jewish plays. Well, sort of.

I don't really like how messy life is, but it is messy, and so I need to clarify this. The first play I ever properly wrote was called "Santa Muerte," and I wrote it for a program for homeless teenagers run by Shelley Winters in Hollywood in the early 90s. But it wasn't so much a play as a series of scenes created out of unstructured improvs, Shelley didn't like it, I didn't like it, it was never produced, and so I don't think of it as being my first play.

No, my first play was written just as "Santa Muerte" was falling apart. I had taken a trip home to Minneapolis and discovered a few pages of something I forgot I had written, and I quickly expanded it into an epic stage play called ""The Substitute Bride."

While the play superficially was a sequel to "Alice in Wonderland," I had been reading a lot of Yiddish theater in translation, and so "The Substitute Bride" is, in its not-well-hidden heart of hearts, my attempt to write a Yiddish play in translation. There is an actual Purim shpiel in it, in the form of a folk tale about Vashti, the first wife of Persian King Ahasuerus in the Book of Esther. Most of the plays characters are Eastern European and unsubtly coded as Jewish, and there is even an armadillo who repeatedly cries out phrases I lifted from Yiddish plays.

I was even more explicit in my next play, "Kishinev," a retelling of the Kishinev pogrom in the form of a Jewish folk tale about a Hasidic woman who marries a rebbe and takes charge of his followers when he dies. This is loosely based on my own family history, as my mother's family came from Kishinev and from an important Hasidic line. There is a lot of Yiddish in the play, and a lot of folklore, and a lot of dramatic scenes I lifted from actual Jewish history.

Neither of these plays have ever been produced, although "The Substitute Bride" had a reading in Hollywood that featured a lot of television actors, and "Kishinev" has a public reading in Manhattan a couple of years ago. Both plays are, by modern standards, largely unproducable, as they feature massive casts and expensive stage action. It took me years to learn how to write a play that can be produced on the cheap.

I did learn, though, writing small plays for tiny casts set in single locations. These shows were not Jewish; my most successful play retold the true and awful story of the lynching of an African-American man in Omaha in 1919. I have written plays inspired by the lives of Truman Capote, Andy Warhol, and Oscar Wilde. I worked at a historical society for three years and this led to writing plays based in local history about Chief Standing Bear and Buffalo Bill Cody.

And, for my own amusement, I wrote a series of plays about performers who have lost their minds attempting to appear in productions that are falling apart around them. These have been really tiny shows, and and have had appropriately tiny productions: One, called "A Stage Reading," was produced in someone's backyard. One, called "NSFW," was produced at the back of a bar. And one, called "Basement Porn Party," was actually produced in a basement.

About a year ago I decided I wanted to start writing Jewish plays again. I had started studying Yiddish, and had also been reading about the various odd forms that Yiddish performance took in the mid-20th century, and so I wrote a play called "Shaina" that, like my other plays, was about a performance falling apart.

The play is somewhat hard to describe. The main character, Shaina, comes from a long career on the margins of Yiddish performance. She has been in Yiddish plays at vegetarian Communist theaters, appeared on a Yiddish radio soap opera about pickle millionaires called "Who Thinks They're Hoitsy Toitsy Now," and wound up performing Yiddish bawdy songs in bathhouses. (This last detail is inspired by Bette Midler, who actually did perform in bathhouses.)

The play climaxes with Shaina hired by Jerry Lewis to write and appear in a Yiddish version of his notorious Holocaust film "The Day the Clown Cried," which somehow she manages to make worse. Now, for the sake of establishing this early on to avoid litigation: I have never seen "The Day the Clown Cried" (nobody has), and the version of the film that appears in my play is both invented and parodic. I also think it ends up being unexpectedly respectful of Jerry Lewis, even considering that his appearance in the play is limited to Shaina doing a terrible impression of him.

So anyway, a few months ago I entered the local Fringe Festival, which happens to be the largest non-juried festival in America, and wound up getting a slot. So I am producing "Shaina."

I am not normally a theater producer. I usually prefer to write plays and then have nothing to do with them, except for showing up a few times to see them. But I have produced plays, or, more often, small theatrical events, and I had a large hand in producing my first play. I will also be directing this production, which I have done a little of, although I might request some assistance on this. And I will be appearing in it, although my role is small and mostly limited to playing a few songs on ukulele.

Oh, did I mention this is a musical? It's a musical. I've written the lyrics for the songs but have not written the melodies yet, but all of my plays are musicals and I have written an awful lot of songs in the past. (If you really dig, you can also find some albums I put out.)

This means that there is an awful lot of work ahead of me before the play actually debuts in August. So I will be keeping a diary of the production of the play, in part just to keep me on track. First, I need to make a list of what I need to do for the show, and that's my moment to shine.

I may not be good at much, but boy can I make a list.

Dress Yiddish Think Yiddish

Dress Yiddish Think Yiddish

I made a decision a while ago to start being more visibly and publicly Jewish. This presented a bit of a challenge to me, as there are some signifiers of Jewishness that already exist, but they either seemed wrong for me or I just didn't like them.

There is, as an example, the yarmulke and the tzitzis, the beanie and fringes that Orthodox Jews wear. But these aren't simply signifiers of Jewishness, but of religious Jewishness, and I am not religious, I was not raised Orthodox, and am not now Orthodox. I used to wear them, by the way, when I was in high school, because I went to a local Yeshiva, so they are something I have experience with, and I do especially like the tzitzis, which are fun to wear hanging down from under your shirt. But it is not a look associated with Jewish atheism, and so would not be right for me.

There is also the Jewish star and the Chai, but, for whatever reason, I just have never wanted to wear either. The star doesn't simply represent Judaism, but is closely associated with Zionism; it was selected as the symbol of the movement in 1897, and is, of course, on the Israeli flag. My feelings about Zionism and Israel are knotty, like a lot of American Jews, and it seems odd for me to wear a symbol that primarily communicates "it's complicated."

I do sort of like the chai -- Elvis wore one later in his life, perhaps as a nod to his own Jewish heritage. But it usually appears hanging at the end of a gold necklace, and I can't, I just can't.

So I have had to sort of come up with my own ensemble. I don't know if it actually screams Jewish to the general population, but it feels right for me.

The basics

The core of my wardrobe now consists of black pants, white shirt, black vest. It's a look that I like to call H&M Hasid, although that's putting on airs. Properly I should probably be called Target-brand Hasid, considering how many of my clothes say Mossimo on them. But, then, Target is a Minnesota company, so it seems right for me.As it is winter. my vests are typically the sporty, stiff collared fleece vests that are sold in hiking stores. One of my brothers dresses pretty much exactly the same way, but it is because he actually does sporty things. He swims and hikes and rides motorcycles, which all seems very irresponsible to me. You could get hurt doing those things.

Anyway, without any additions, I just look like anybody in black pants, white shirt, and black vest, and, God forbid, somebody might even mistake me for a hiker, so I have some additions. Here is the most important.

The fiddler cap

This is called the fiddler cap because of Fiddler on the Roof, of course. Tevye wore what looks to be a linen one, one of the occasional filmic nods to his middle class aspirations (he also may sing about wanting to be rich, if I remember right), while the revolutionary Perchik wears a leather onelike some sort of Ukrainian Marlon Brando.

The hat is properly called a maciejówka, which is a traditional Polish cap, and if you look at pre-war photos of Jews in Eastern Europe you do see quite a few of them wearing one version of the maciejówka or another -- although you also see a surprising number of them wearing what seems to be a variation of the woolen karakul that comes from Afghanistan, and, of course, plenty of delightful fur hats. They hadn't reached the size or shape of the modern shtreimel, which looks like a flying saucer made of fur has landed on a Jew's head, but they look terrific nonetheless.

Shtreimels are worn by married men, and by hasids, and, again, I don't want to send the wrong message. Also, they cost, like, $3,000, and I don't have that kind of money. So fiddler caps it was to be, and fiddler caps it is. I have about five now, and I especially like them because John Lennon used to wear one, so it fits in with my "Dress British" theme.

All by itself, the ensemble does make me sort of look like a 19th century Greenhorn went to Walmart and just bought what was familiar to him. But an ensemble is made by its accessories. So let us move on to the pins and buttons.

The pins and buttons

I have three places I affix pins and buttons. First, there is my coats, which I have not discussed, but they are all black and long like a caftan, except that one is a duffel coat, one is a raincoat, and one is the sort of thee-quarter-length black leather coat worn by gangsters in 1970s films.I was going to go with a theme for these pins I call "mine bubbe's tam," which means "my grandmother's taste." So on one I have a pin of some challah, and on another I have a bundt cake, which was invented by the Hadassa of Minneapolis just a few blocks from where I am sitting. But then I also found an attendance pin from a synagogue, and it was so delightful that I put it on my gangster jacket.

I also put pins on my vests. Here I decided to wear flags from the various countries my ancestors came from: Ukraine, Belarus, Moldova, and Poland. This is not something typically done by American Jews. You don't often find American Jews lingering at Polish-American halls, as an example, and this is understandable. It is hard to think of yourself as Polish when the country had a long history of antisemitism and participated in your murder.

But my mother's father came from Warsaw. He had a specific history in a specific place, and I wear the pin to remember that, and also to signal that I am from an immigrant family, which seems like something that is especially worth signalling when there is so much nativism around nowadays.

Finally, I wear pins on my hat, and here I decided to most clearly signal my politics. At my core, I am an anarcho-socialist, although, in practice, I'm just a very frustrated liberal. Nonetheless, I have pinned a black rose to one fiddler cap, a black cat to another, both traditional anarchist images. On the cap I'm wearing today I have an antifascist symbol, which, prior to the past few years, might have felt like the sort of thing a historical reenactor would have favored, but then fascism sort of became mainstream again.

Oh, and there is one more element to my wardrobe. The socks.

The Socks

As Albert Goldman says in "The Birdcage," one does want a hint of color. All of my socks are British flags. My father noticed this a few days ago and shook his head. "Dress British Think Yiddish," he said.He gets it. He doesn't seem to approve, but he gets it.

Year 2, Week 11: The Chaos

Year 2, Week 11: The Chaos

The stats:

I have studied Yiddish for 412 days

I have studied Yiddish flashcards for a total of 260 hours

I have reviewed 4,678 individual flashcards

I have mentioned my dog, Burt, in the past. Burt is a rescue dog, and, when we first got him, almost a year ago, he was a mess. He was twice his body weight, he had just had an eye removed, he did not know his own name, he was not really house trained, and, further, he wasn't anything trained.

Burt has benefited from a regular schedule, some of which he made up on his own. For instance, he tends to wake up between five a.m. and six a.m. and demand to get into bed with me, unless he is already in bed with me, in which case he will sometimes jump out of bed, wander for a few minutes, and then demand to get back in.

We feed him twice per day, which was new to him. We walk him four times per day, and try to make his third walk, in the late afternoon, especially long to tire him out, or he will spend the next few hours moving our shoes around, digging tissues out of the garbage to tear up, barking with frustration at the garbage can when he can't get into it, and otherwise getting into mischief.

When we have had to change Burt's schedule, things have gotten chaotic. He's still not clear on why he can't pee inside the apartment, so we need to make sure we stick to his walking schedule. If we take an afternoon nap with him, his early evening mischievousness is magnified, because he has so much energy. He came from chaos, and, without structure, easily reverts back to chaos.

I mention this because it is all true of me too. Well, not the peeing in the apartment, but most of it.

If I don't get to sleep early enough, I wake and cannot focus on studying Yiddish. So I will decide to nap, figuring I can always get back to it. And then I will get back to it too late, and not finish it, and words I am studying will get pushed back to the next day.

The next morning, the amount of Yiddish I must study will be more than I have time for before I must go to work, and so I will put it off until the evening, and I will forget until the last minute, and more words will get pushed to the next day. So I will not add any new words, figuring 200, 250 old words are more than enough for me to do in one sitting, and I won't get them done. So maybe I need to not add any new words for another day?

This was last week. I finally nailed it all down a couple of days ago, getting caught up on my studies, but, man, it took me back. Years ago, it felt like everything had that sort of quality, like everything in my life was a growing avalanche of overdrawn bank accounts, unpaid bills, untidy apartment, incomplete projects.

I did not like it, and, in my late 20s, later than I should have, I set out to change it. It took most of a decade to unlearn bad habits and learn good ones, which was tremendously frustrating, but, as things became less chaotic, I found myself getting more done. I wrote plays and got them produced. I managed to move from being a cashier, which I did throughout my 20s, to being a journalist, which I have done ever since. Like the dog, I needed structure, and, unlike the dog, I had to impose it on myself.

The thing is, old habits don't really go away. I can always feel the chaos creeping at the edges of my world. I know that, without these little, ridiculous tools I use to try to keep my life from going off the rails -- numbered lists of things I need to accomplish, etc. -- my life would go off the rails.

It hasn't been easy fitting Yiddish into all this. It is hard work -- much harder than I expected. It requires at least an hour a day, and, when there is a lot you want to do, seven hours a week is an awful lot to carve out. Worse still, I have mostly made up for the missing time through lack of sleep, and lack of sleep is a great way to let the chaos in.

On the other hand, studying Yiddish has also forced me to be even more precise in how I schedule my day. More than that, it has forced me to think about how I schedule longer stretches of time. I have not been a patient man in the past, and could rarely sustain any single project for a few months, much less a year.

But I noticed over time that the really important projects, the really significant ones, generally took years, and sometimes decades. They took someone committing to the project, and pursuing it, sometimes without any end goal or without any visible accomplishment. They did so because the project itself was valuable enough that it didn't matter if there was any big payout at the end, or where the project was going. It was just worth taking the time to do.

I needed to learn how to do this. In the long run, it is less important that I now know the Yiddish word for maniac (I learned it this morning, and it's maniak) than the fact that I am doing something that is very hard over a very long time period.

Although, that being said, I do like knowing the Yiddish word for maniac.

The Golem and the Mock Wedding

The Golem and the Mock Wedding

Azoy.

There used to be a thing in the Catskills, now mostly forgotten, like a lot of Catskills things. It was a mock wedding, which Phil Brown writes about in his book "Catskill Culture: A Mountain Rat's Memories of the Great Jewish Resort Area."

He called the mock wedding "curiously common in Catskills resorts, a burlesque form with switched sex roles and rabbis speaking Yiddish gibberish."

"Why was the mock wedding so popular?" he asks. "It enabled people to stage an event that reminded them of Lower East Side Jewish vaudeville houses, without having to possess either music or comic skills, and without having to hire any entertainers. As well, the mock marriage was an ethnic self-criticism of the tradition of arranged marriages; in the new world, without the customary arranged marriage, the very institution of marriage could be mocked."

Brown recalls one wedding in which was man was the bride, the groom was a woman, and the ring was made of raw potato. It's possible to see moments of a mock wedding in the 1982 documentary The Rise and Fall of the Borscht Belt, and the image is as garish as an underground cartoon, including a pipe-smoking hillbilly following the bride and groom with a shotgun.

For those who wish to experience the real thing, however, there will be a Catskills-style mock wedding March 23 in New York City with the band Golem.

This will be the second time they have thrown a mock wedding, but have not done so since 2005, so this is a rare event. I will be in New York that weekend, but stupidly reserved a flight for the following day, so I instead spoke to Annette Ezekiel Kogan, the band's founder, about the event.

"I feel like I'm planning a real wedding," she told me, sounding exhausted. She would not share a lot of the details, except that there would be a groom, a bride, a flower girl, a wedding cake, and a band member would be the rabbi. She also allowed that there would be cross-dressing, and that much of the performance would be the badeken, the ceremony in which the bride is veiled and marched to the huppa.

Afterwards, there will be a dance, the way there are at weddings, even mock ones. This is something Golem has a lot of experience with: It is still possible for bands to make a living on the events circuit in and around New York, playing bar mitzvas, weddings, anniversaries, and the like.

Golem does these sorts of events, which allows the 17-some-odd-year-old band to make music full-time; attendees at the mock wedding will be able to see the sort of mix of Golem playlist and party music that the band provides when working an event.

For those unfamiliar with the band, Golem started out as the result of Kogan's various interests and studies, which included Slavic languages, Yiddish, and Ukrainian dance. "I had no interest in doing original songs," she told me, but, after a while, a vision for the band coalesced -- a multilingual, modern, frequently raucous spin on traditional Jewish and European music. "I imagine of the Holocaust hadn't happened, this is the sort of music that might have happened," Kogan says.

As to the name of the band, Kogan explains that they started performing shortly after a trip to Prague, the home of the mythical Jewish monster. "It just seemed like it was all about golems," she says.

I remain a little surprised that every single klezmer band hasn't called itself Golem. "No, just us," Kogan says. "There is a German Death Metal Band called Golem, but we have very little to do with each other."

"I think they should just give us the name," Kogan says. "For reparations."

For more information about Golem or their March 23 mock wedding, visit their Website.

Guillermo del Toro at MIA

Guillermo del Toro at MIA

Film director Guillermo del Toro has an exhibition at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts just now titled At Home with Monsters. It's the second stop for this show, which originated at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, although, really, it originated with a Los Angeles house del Toro owns that he calls Bleak House, after the book by Dickens.

Del Toro is a consummate collector. "If you give a Mexican three objects, he will make a shrine," he told a crowd at MIA on opening day, and he prides himself on reflecting the shrine-like ulrabaroque sensibilities of Mexican artists. Del Toro has collected since he was a boy, mostly work related to the supernatural and especially related to the supernatural in film, and his collection has grown so large that it has its own house. Bleak House.

I attended the exhibit on opening day, listened to a talk del Toro gave, got him to sign a book, and then, just by a stroke of luck, found myself part of a private tour of the exhibit led by del Toro. He was uncommonly generous, spending an hour and a half, almost two hours explaining his collection. There were original designs for Disney films, original cartoons by Richard Corben and Gahan Wilson, uncannily realistic sculptures of H.P. Lovecraft and Edgar Allen Poe, and original costumes and props from del Toro's films. He had stories about all of them, and could minutely detail the process by which the art was made, and offer biographies of the artist.

Del Toro is, himself, a filmmaker of indulgent detail. Superficially, many of his film seem to be pop confections, enjoyable but slight cartoon glosses on established horror tropes. (I am referring to films like the Hellboy movies and "Pacific Rim" here; his "The Devil's Backbone" and "Pan's Labyrinth" are undisputed masterpieces.)

But even those film are crammed with significant details, and, on each viewing, the films grow deeper as his talent for visual storytelling comes to the fore. Characters who appear for only a moment grow in significance when we notice these details, like the Russians in "Pacific Rim" who pilot a giant robot, and who are literally welded into its stomach; they have no possibility of escape, so every battle is to the death. They are onscreen for perhaps two or three minutes, but have become fan favorites due to the amount of information it is possible to glean in that time.

Del Toro is a pop filmmaker, and yet he is one that his fans feel a private relationship with, thanks to these details. It is as though his films are full of secrets, available for those who care enough to dig, and eventually you find a secret intended specifically for you.

Examples: Disabled audiences noticed that the two scientists in "Pacific Rim" have disabilities, and how, despite their rancorous relationship, they demanded respect for the other's disability; The class conscious noticed that Idris Elba played his role with his native, working-class Hackney accent; Feminist audiences noticed that Rinko Kikuchi's character was secretly the star of the film, and Japanese audience noticed that her most significant moment was presented in untranslated Japanese.

So here's the secret that is speaking to me just now, and it isn't such a big secret, but it seems especially meaningful to me just now, and it's the reason why I feel this discussion belongs on a Jewish blog. Del Toro is one of the few filmmakers working today who shares a certain sensibility with the horror films of the 30s and 40s, and that sensibility is as follows:

Fascism is a terrible thing and it must be resisted.

I'll start with the old movies. Horror developed as a genre at the exact moment fascism rose in Europe, and often seemed to reflect on the fact, detailed in the book "From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of the German Film" by Siegfried Kracauer.

It was there in hints in the early films, including "Dracula," which used the same sorts of motifs of blood-sucking vermin that the Nazis favored, but made the villain European royalty, rather than Jews. There was "The Invisible Man," in which a lunatic plotted to rule the world through a campaign of terror. As more of these films were made, they became a shore upon which dozens, and eventually hundreds, or European filmmakers washed up, seeking refuge from European fascism.

As this happened, the themes became more visible and obvious, including "The Wolf Man," in which a poisonous savagery spreads through Europe (marked by a star on the body); and "The Black Cat," in which Bela Legosi arrives to take a terrible revenge on a war criminal, played by Boris Karloff.

Del Toro has unambiguously addressed fascism, setting two of his films, "The Devil's Backbone" and "Pan's Labyrinth," during the Spanish Civil War. "Hellboy" is set in the shadow of the Holocaust, with the occultist German Thule Society (a predecessor to the Nazi Party) rising up to bring about genocide. Even "Blade 2" based itself around a disastrous eugenic experiment designed to breed a master race.

Del Toro speaks often about fascism, and how, in his films, the monsters are rarely the villains, but, instead, it is humans who are often the most monstrous. "What interests me about fascism is that it is a black hole of free will," he has said. "It is a system which isn’t necessarily unique, but it absolves brutality, it absolves the lack of morals and it absolves people of their own decisions. When they tell you ‘you can kill these people because they are Jews, reds or homosexuals, or whatever!’ In this world you can permit a brutal action on the base of collective advice; that is what scares me."

He understands the appeal of fascism: "One of the dangers of fascism and one of the dangers of true evil in our world—which I believe exists—is that it's very attractive. That it is incredibly attractive in a way that most people negate. Most people make their villains ugly and nasty and I think, no, fascism has a whole concept of design, and a whole concept of uniforms and set design that made it attractive to the weak-willed"

He is open about the fact that he uses horror as a metaphor for addressing fascism, saying "What I really set out to do with 'Pan’s Labyrinth' was to make an anti-fascist fairytale — which I think is very pertinent to our times right now! I really like exploring big, political events through metaphors, and I think horror is a very political genre."

And what interests me about del Toro's film is not merely that their look into fascism, but also the way they prioritize resistance to fascism. The woods in "Pan's Labyrinth" is filled with guerillas, taking up arms against Spanish fascists, while a quieter revolution goes on inside the house of one of the fascist leaders. In it, his housekeeper is secretly a revolutionary, while his daughter slips into a metaphoric realm in which she is constantly confronted by appealing demands to do evil.

This feels like a time when we need movies that recognize fascism as a breeding ground for monsters, and celebrate resistance to it, even if that resistance is imprecise, or metaphoric, or suicidal. Because del Toro's films also show us what the world looks like after fascism: A wasted place of mass death and abandoned weapons that still might become deadly at any moment.

This world. Our world.

It has real monsters in it, and someone really does need to stand up to them.

The 100 Yiddish Words Everyone Should Know: Kvetch

The 100 Yiddish Words Everyone Should Know: Kvetch

I'm going to reclaim the word kvetch. It is inarguably one of the definitive Yiddish words, but I don't like how it has been defined. It's a word to describe a complain, or a complainer, and there is often a sense that the complaint is both irritating and ineffectual. That's how Wiktionary defines it: "To whine or complain, often needlessly and incessantly."

But Yiddish has other words for this. There is grizhen, which literally mean to gnaw, but it used to mean to nag. Nags are constant, and nags are frequently ineffectual, or they wouldn't need to nag.There's also nudge, which probably literally means both to bore and to be a pest. An ineffectual complainer is a nudge.

Jews are complainers, but our reputation is not as nags or nudges. No, we have a reputation for really being able to dig in with our complaints, to get a reaction. What is the stereotype of the Jewish mother but that of someone for whom a complaint is a tool, and who uses it as a master. Here's a classic Jewish mother joke:

Q. How many Jewish mothers does it take to change a light bulb?

A. Never mind, I'll sit in the dark.

It's a complain without complaint, a complaint in which both the problem and the solution are implied, but also demanded. Jewish mothers aren't the only ones to do this. Here's another joke:

A Jew calls his waiter over. "Taste my soup," he says.

"Is it the wrong soup?" the waiter asks.

"Taste it," he says.

"Is it too salty?" the waiter asks.

"Just taste"

"Is there not enough chicken?"

"Taste."

The waiter looks around. "Okay, I'll taste. Where is the spoon?"

"Aha!" the Jew says.

Again, no actual complain is articulated, but the kvetch is there. Yiddishist Michael Wex identified it as one of the definitive Jewish behaviors, titling his bestselling book on Yiddish "Born to Kvetch." He presents complaining as a sort of Jewish martial art, a duel of competing desires:

"Not only do Judaism in general and Yiddish in particular place an unusual emphasis on complaint, but Yiddish also allows considerable scope for complaining about the complaining of others, more often than not to the others who are doing the complaining. While answering one complaint with the other is usually considered excessive in English, Yiddish tends to take a homeopathic approach to kvetching: like cures like and kvetch cures kvetch."

Kvetch, it should be noted, doesn't mean complain. It means squeeze or press. The proper kvetch applies pressure, again like a martial art. You find the weak point and crush it. Guilt? Apply guilt. Shame? Apply shame. Fear? Make them afraid.

Guilt usually works, though. I read a story recently from a fellow whose father took care of rental properties. When clients wouldn't pay up, he would call and say to the, what are you doing? What are you doing to me? Are you trying to make me into a landlord?

They always paid. I don't know if the rental manager in the story was Jewish or not, but I do know he knew how to kvetch.

This is why I want to reclaim the kvetch: Because it is the tool of the powerless. If you're a European Jew, from the past few centuries and something goes wrong for you, there is not a lot of recourse. The authorities don't much care about your problems, or for Jews in general. Other Jews are looking after their own concerns, and the Jewish court is often a useless morass of singsong legalism. You probably don't have any social position, you probably don't have any money, and, unless you're a gangster, you probably aren't going to get very far threatening to beat someone up. So what do you do if you have a problem?

You squeeze. You make sure you're the bigger problem, and that the problem gets taken care of just to get rid of you.

Do this poorly, and you're a gnawer, a nag, a nudge. Do it well and you're something else. You're a superlative complainer.

You're a kvetch.

Some uses of the word kvetch:

Portnoy’s Complaint, Philip Roth "Is this truth I’m delivering up, or is it just plain kvetching? Or is kvetching for people like me a form of truth?"

Graphic Details: Jewish Women's Confessional Comics in Essays and Interviews, interview with Lauren Weinstein: "Maybe it's the idea of making something funny and sad -- that funny and sad are basically the same thing. Maybe because Jews like to kvetch a lot, there's a kvetching aspect to the work."

Broken Glass, Arthur Miller: "Hitler? Hitler is the perfect example of a persecuted man. I've heard him -- he kvetches like an elephant was standing on his pecker. They've turned that whole beautiful country into one giant kvetch!"

Year 2, Week 10: That goddamn word

Year 2, Week 10: That goddamn word

The stats:

I have studied Yiddish for 405 days

I have studied Yiddish flashcards for a total of 253 hours

I have reviewed 4,633 individual flashcards

So there is a Yiddish word that essentially means "flier" or "broadsheet." It's not a word that has that much use in my world, but in the Haredi world there is a long history of these sorts of broadsheets. They are a cheap, effective, and frequently anonymous way of communicating, and so there will sometimes be wars of opposing broadsheet hangers who launch missive after missive against each other, all hung from bare walls or telephone poles or the like.

For some reason, I stuck this word in my flashcards rather early on, and it has been an irritant ever since. I just can't memorize it.

I want to memorize it, because I like this sort of word, a word that is associated with a specific cultural expression, and, who knows, some day I might want to get into my own broadsheet war. I have made efforts to memorize it, trying various mnemonics and then just trying to force it into my memory by brute force, repeating it over and over again, tens of times, hundreds of times.

None of it worked. The word would pop up in my flashcards and I would draw a blank, and then I would curse myself and consider authoring a broadside directing angry words at my own brain.

Yesterday I was on the bus on my way to work and suddenly my brain said a single word. "Pashkevil," it said. It was that goddamn word.

And I knew it. I knew that I knew it. From that moment on, it would be easy for me to remember it, instead of impossible. And it has been. I just used it with my boss. We published a story he fears might upset the Haredi community, and I told him we'll know we did if pashkevils show up on our door.

I have had this happen before. A word will just spontaneously go from being unmemorizable to unforgettable, and often like this, just by popping into my head at the odd moment. There doesn't seem to be any set length of time either -- I think I have been trying to memorize this word for a year. This is the longest it has taken, and so stands out. I wonder if there are words it will take me two years, three years to learn?

Memory is strange. My father has been complaining about his memory lately. He always had a very fine memory, and now he struggles to remember the sort of things we all struggle to remember. He told me he can't remember the name of the black actor from The Shawshank Redemption, and so he uses his own mnemonic: The Yiddish word for morning, which is morgan. I feel like if he is using Yiddish words to remember English words, he is probably doing all right.

Now, whenever I hear Morgan Freeman's name, I think of Yiddish. Nobody warns you this is going to happen when you start studying a language.

A Yiddish takeover of Wikipedia

A Yiddish takeover of Wikipedia

I used to contribute to Wikipedia now and then. I'd just write up posts on things I thought were interesting, and the forget about them. I went to read up on Nudie Cohn, the creator of the rhinestone cowboy look, and then remembered that I had written the article, although it has been expanded upon and improved in the ensuing years. I also wrote the original article about sideshow performer Johnny Eck, and sort of forgot to finish it. Other people finished it for me.

I occasionally write that I always meant this blog to be activist: It was intended to encourage people to walk away and do something Yiddish. I don't know how successful I have been at that, as I tend to fall back on the sort of things I have always done: Writing about movies, pontificating about politics, etc.

But I decided to personally become more activist this year, in that I would do Yiddish things away from the blog and report back on them. One of these things has been to start writing Wikipedia articles again. So far I have authored an article on Yiddish cabaret performer Pepi Litman and an article on an alternative to Zionism that never really took off, called Golus nationalism.

I'd like to encourage readers to do likewise. Like it or not, Wikipedia is the fifth most-visited website in the world, and certainly the most popular reference source. Speaking as a newsman, you'd be surprised how many news articles are pieced together from various Wikipedia articles. I'm sure this is also true of high school essays, works of historical fiction, and, I don't know, maybe lyrics to popular songs. I suspect bits of Wikipedia get everywhere, like those weird bits of code in DNA that come from worms or viruses or whatever.

So, in a very real way, if something isn't on Wikipedia, it doesn't exist in the same way. It doesn't come up in searches in the same way, it is invisible to a lot of people who use the web, and it doesn't get to weave its way into the larger discussion the way Wikipedia articles do.

I'm not the first to discuss this. If you look up WikiProject, you'll find a variety of attempts to address what has missing or minimized on the site. As an example, women scientists. There's also the Women in Red project, which was developed in response to the fact that only 15 percent of the biographies on Wikipedia were about women. There have been projects, with varying levels of success, to add and improve articles on the LGBT community, ethnic groups in general, and various niche interests, including specific televisions shows, the subject of martial arts, and the game of snooker.

There aren't that many Wikipedia pages about Yiddish or Yiddishkeit. There's what you would expect: A general introduction to the language, English words derived from Yiddish, and then some superficial introductions to Yiddish's most famous topics, like theater, klezmer, and literature. Some of these are well-written, some are stubs, and they tend to suffer from the same failings as the rest of the site.

There is a tendency to focus on men, as an example, although not the the extent of the rest of the site: On the Yiddish theater performers site, there are about 32 women to 55 men, so 36 percent, if you ignore the fact that the Barry Sisters are represented three times on the page.

Still, there is always room for improvement. Until I added Golus nationalism, Zionism was the only example of Jewish nationalism on Wikipedia, and Zionism rejected both Yiddish and the Diaspora experience, both of which Golus nationalism embraced. And while Golus nationalism never found the following Zionism did, if we are to discuss alternatives to Zionism for Jews who have no intentions of moving to Israel, and want to be able to maintain a Jewish identity as part of a minority inside a largely non-Jewish nation, it helps to have access to previous generations of thought about the subject. Especially when, like me, your concern is Yiddish, and that thinker addressed the subject of Yiddish.

I don't know what else I will add to Wikipedia, but I have committed to adding 25 new articles on Yiddish topics. This is something anybody can do -- one need not be an expect on a topic to start a Wikipedia page, and, as with my Johnny Eck page, you can even forget to complete it and somebody will come by and fill in what you missed.

Wikipedia is not terribly difficult to use, although they have their own conventions, which they will try to walk you through. I haven't mastered them, and every so often I notice a Wikipedia adminstrator has left a note on my page telling me that I forgot to do something, or should add something, and I generally do whatever they say.

Wikipedia has some general guidelines for what makes a good article, and they are worth familiarizing yourself with, because, boy, they will delete an article that doesn't fulfill these requirements. That being said, Wikipedia admins do not seem nearly so trigger happy with deletions anymore, and the site generally gives users the opportunity to fix an article before it is deleted, assuming the article isn't total garbage.

There is also a Yiddish-language version of Wikipedia for advanced speakers. I am nowhere near ready to tackle that, but perhaps someday.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Pages

Popular Posts

- I Married a Jew

- The 100 Yiddish Words Everyone Should Know: Goy

- The 100 Yiddish Words Everyone Should Know: Pisher

- The Top 10 Yiddish Words You Need to Know

- Guillermo del Toro at MIA

- The 100 Yiddish Words Everyone Should Know: Plotz

- The 100 Yiddish Words Everyone Should Know: Kishke

- The 100 Yiddish Words Everyone Should Know: Shtup

- On Allyship

- On allyship: Shutting down debate

Powered by Blogger.